resilience | thinkthinkthink #8

redundancy & adaptability in complex systems.

"A complex system can explore alternatives while exploiting what it already finds useful." - John Holland

Long-lasting social, political and biological systems share one principal common denominator: they are redundant and adaptive. These systems exhibit stability brought about by multiple contingencies. Simultaneously they invest in improvement through repetitive low-risk behavior. Resilience is inherent to complex systems - the more redundant a system is, the less it is prone to fail completely. The consequences of failure are typically catastrophic; therefore these systems iteratively learn to defend themselves through marginal improvements. They develop a series of diverse tactics that compensate for one-another's failures.

"Each of these small failures is necessary to cause catastrophe but only the combination is sufficient to permit failure." - Richard Cook

This approach is sometimes referred to as the swiss-cheese model - most of us have recently encountered it illustrating viral proliferation. Masks, social-distancing or handwashing each contribute in different but correlational ways in halting infection.

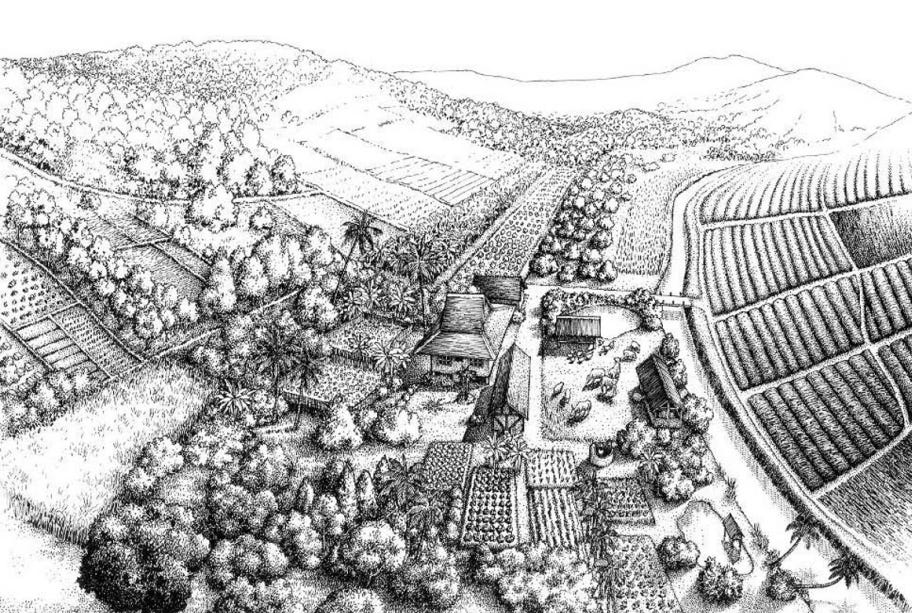

This strategy is bound to appear in adaptive systems on long enough time scales. One interesting example is the variety of agricultural plots in olden villages where households farmed small strips of land in different ecological micro-zones. This meant that a family would have to tend to a dozen different crops located in various locations. While this strategy might be inefficient, it also distributed risk and therefore hedged against the ultimate threat: total crop loss & famine. At high altitudes, the human body behaves similarly when confronted with low oxygen: it increases the rate of respiration, changes the pH of the blood, and radically boosts the number of oxygen-carrying red blood cells. This process takes weeks, but evolution has - over time - ingrained resiliency to high altitude.

Differing from most biological complex systems cities never seem to die of old age - the few cities that have disappeared in history are outliers. The secret behind urban resilience is a city's ability to adapt to change.

There are, of course, classic examples of cities that have died, especially ancient ones, but they tend to be special cases due to conflict and the abuse of the immediate environment. Overall, they represent only a tiny fraction of all those that have ever existed. Cities are remarkably resilient and the vast majority persist. Just think of the awful experiment that was done seventy years ago when atom bombs were dropped on two cities, yet just thirty years later they were thriving. It’s extremely difficult to kill a city! - Geoffrey West

From our limited perspective these transformations might seem invisible. Cities - like most sophisticated systems - adapt through a large number of small bets. This is a rather conservative model but in the long term it is the most efficient. Individual agents in cities routinely explore potentially successful niches with little cost to the system as a whole; a similar behavior to informal systems previously discussed in thinkthinkthink. For example, a citizen could invest her life-savings in starting a new business that could grow into an important enterprise for the city-coffers. The city stands to gain, while only the citizen stands to lose if said business fails. Similarly, while founders might go all-in on their startup, VC angel investors place a large numbers of small bets, capitalizing on the ones that succeed.

In Life's Information Hierarchy, Jessica Flack describes how slow variables promote accelerated rates of adaptation:

Slow variables facilitate adaptation in two ways: they allow components to fine-tune their behavior, and they free components to search, at low cost, a larger space of strategies for extracting resources from the environment. This implies that over evolutionary time, structure changes more slowly than sequence, thereby permitting sequences to explore many configurations under normalizing selection.

Citizens are the individual agents, the components of the city as a slow variable. Planning should at-best attempt at stimulating new sequences: local, small-scale, diverse. If any prove successful the city will slowly metabolize them in the long-term. Cities are living entities always changing and adapting to new environments. They do not have resting points and do not strive towards any simple kind of equilibrium. Constant adaptability is a feature of long-term success.

Did you like this issue of thinkthinkthink? If so consider sharing it with your network:

Links

What Is It Exactly That Makes Big Cities Vote Democratic? by Richard Florida

A relevant (old) take on the geography of class & urban-rural political divide

How 30 Lines of Code Blew Up a 27-Ton Generator by Andy Greenberg

On the lethality of GIFs

Amazon is a less efficient company than Walmart by Andrew Sentance

An interesting take on dis-economies of scale

Tweets

This was the eighth issue of thinkthinkthink - a periodic newsletter by Joni Baboci on cities, science and complexity. If you really liked it why not subscribe?

Thanks for reading; don't hesitate to reach out at dbaboci@gmail.com or @dbaboci. Have a question or want to add something to the discussion?